An important new Special Report in the Poughkeepsie Journal documents the increase in suicides in New York State prisons–and its relationship to solitary confinement. The reporter, Mary Beth Pfeiffer, has a long history of documenting the plight of people with mental illness in the criminal justice system. For this latest report, she filed FOIA requests and compiled her own data to show the connections between mental illness, inadequate care, solitary confinement, and prison suicides, which persist in spite of recent measures meant to improve mental heath treatment in the state prison system.

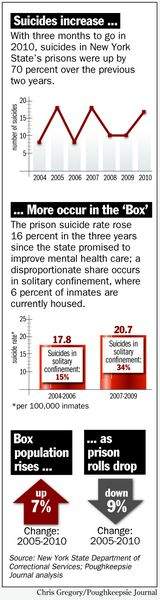

The recent suicide of a young woman at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility for women, Pfeiffer writes, “is one of 17 in state lockups so far in 2010 — 42 percent above the annual average for the past decade and, as of mid-October, a 70 percent increase over all of 2009.” She continues:

The rise in prison suicides comes three years after the state settled a federal lawsuit over prison suicides and after changes that officials say — and lawyers for inmates generally agree — have improved state prisons for inmates…who suffer serious mental illness. Among these, about 400 treatment beds have been added for schizophrenic, severely depressed and bipolar inmates…

“Four recent evaluations show not only an improvement of the services to the mentally ill but also demonstrate a greater sensitivity to the needs of the mentally ill inmates,” according to a fact sheet issued in 2009 by the state Department of Correctional Services.

But the changes aside, a Poughkeepsie Journal review of documents obtained under the Freedom of Information Law shows suicide rates actually rose 16 percent for the three years before the lawsuit settlement compared with the three years after — from 17.8 suicides per 100,000 inmates to 20.7. As significant, in the three-year period, five times as many suicides per capita occurred in solitary confinement — what inmates call the “Box” — than in the general population.

Since the agreement was signed in April 2007 by the state and a disability-rights organization representing inmates, about one-third of suicides occurred in the Box — the same as in the latter half of the 1990s — even though only 6 percent of inmates were housed there. At the same time, average Box sentences were unchanged from 2005 to 2009, at 112 days, though officials said they are declining for inmates with mental illness.

Most significantly perhaps, mental health care was criticized — sometimes scathingly — in nine of 21 post-settlement suicides investigated by the state Commission of Correction, a three-member board appointed by the governor that oversees correctional facilities.

Pfeiffer examined the individual suicide reports produced by the Commission of Correction. She summarizes them here, in stories that reek of anguish and desperation. The stories, and her analysis, draw a clear connection between suicides and confinement in the state’s Special Housing Units, or SHUs. Her article continues:

Of great concern to inmate advocates is what they see as overreliance on solitary confinement as a form of punishment and control. Figures show that even as the prison population dropped by 9 percent statewide from 2005 to 2010, the population of inmates in the Box rose 7 percent. Put another way, the proportion of inmates in solitary rose from 5.3 percent in 2005 to 6.3 percent in 2010…

[W]ith one-third of suicides continuing to occur in solitary confinement, Jennifer Parish, director of criminal justice advocacy for the Urban Justice Center, an inmate-advocacy organization in Manhattan, said, “Clearly, the appropriate response is to re-evaluate the use of prolonged isolation and to develop less dangerous ways of managing prisons.”

Indeed, the commission reports suggest that consignment to the Box may be a factor in suicides.

In one report, the commission said that Ricardo Cuesado, 33, hanged himself in 2008 during an “extensive punitive segregation sentence,” noting a “failure to adequately assess a clinically depressed inmate” and to provide mental health services.

Other cases involve even short stays, however. In one, a 48-year-old inmate at Fishkill Correctional Facility in Beacon, Larry Chapman, hanged himself in 2009 after only a week in solitary; he had been hearing voices, according to an oversight report of his death. Another inmate, Philip Kedaru, 31 and serving a sentence for robbery at Mid-State Correctional Facility in Oneida County, said he “didn’t know” whether he could adjust to solitary — and hanged himself in 2007 after less than two hours there. Both cases were closed without any fault assigned.

In an article earlier this year, “Locking Down the Mentally Ill,” Solitary Watch reported on the movement in New York to create alternatives to solitary confinement for prisoners with mental illness. The “Boot the SHU” movement gained impetus from a grim 2003 report by the Correctional Association on the state’s Special Housing Units. (The association’s Executive Director, Robert Gangi, would later describe placing mentally ill inmates in solitary as “state-inflicted brutality.”) The lawsuit settlement with Disability Advocates created several hundred new beds in dedicated mental health units and demanded more treatment for prisoners with mental illness who remain in SHUs. A state law that goes into effect next year is supposed to bring about more improvement.

But the Correctional Association found that fully one-quarter of th 5,000 prisoners in New York’s SHUs suffered from serious mental illness, which is considerably more than state figures suggest. Pfeiffer writes that “legal advocates fear that though care has improved, some ill inmates fall through the cracks.” She continues:

Sara Kerr, an attorney for Legal Aid Society of New York, which assisted in pressing the lawsuit against the state, said the addition of treatment beds and staff means “the system is clearly improved.” But, “accurate, appropriate diagnosis and [seriously mentally ill] designation remain a concern,” as does the movement from solitary of inmates whose mental state deteriorates.

The persistent–and potentially deadly–flaws in the system are revealed in a statement from Richard Miraglia, associate commissioner of forensic services for the state Office of Mental Health. According the Pfeiffer, the statement was issued “in response to the Poughkeepsie Journal‘s questions on prison suicides, in particular the high proportion among inmates in solitary confinement.” Miraglia’s statement begins:

Inmates in (solitary confinement) are at increased risk because a majority of inmates confined (there) have personality traits consistent with those found among others at high risk for suicide — male, young and impulsive. Add in the research that indicates that violent offenders are at greater risk for suicide, which many [solitary confinement] inmates have histories of, and are placed in single-cell locations usually after a significant event, and we see an increased risk…

Miraglia’s statement does not mention that prisoners with mental illness are also more likely to end up in solitary. But the message is nonetheless clear: Those prisoners who are most at risk for suicide are often placed in the precise place where they are most likely to commit suicide.